The only person – probably – ever to give a speech at the United Nations featuring a plastic poo, Valerie Curtis, who has died aged 62 of cancer, was one of the world’s first “disgustologists” and was dubbed by her fans the “Queen of Hygiene”. A behavioural scientist, she devoted her career to researching and championing hygiene, sanitation and behaviour change.

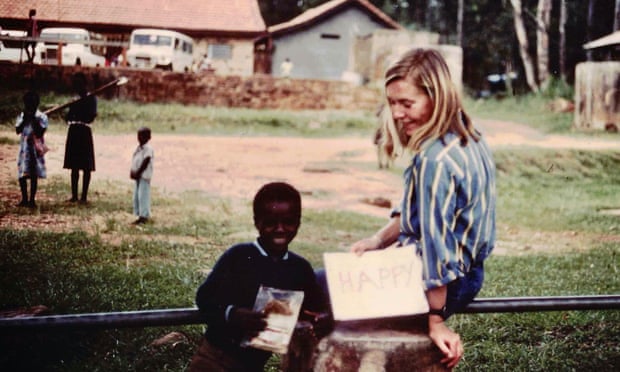

Val began her career as an architect at Arup Associates, working on the new British Library, before her desire to make a greater difference drove her to take up posts with international NGOs such as Oxfam. She worked in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda throughout the 1980s, often in conditions of famine and civil war, installing water pumps in remote communities. It was there that she developed her interest in behaviour.

For most of the 90s Val was in Burkina Faso, working on studies to understand risk factors for childhood diarrhoea. There she met her first husband, Moctar Sacande, and raised two children, Naïma and Abidine. She came to realise that health education was not enough to change people’s behaviour. This insight led to her later career focus on how to use emotions such as disgust to drive behaviour change.

Moving back to the UK in 2000, Val found her academic home at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), where she demonstrated a rare ability to combine science, communication and practical wisdom to become a pioneer in the field of water, sanitation and hygiene (Wash). She became director of the environment health group at the school and was appointed professor of hygiene in 2016.

Her unusual multidisciplinary background gave her the intellectual flexibility to move comfortably between being a world-class academic, and an adviser to governments, international agencies and the private sector on how to promote safe hygiene and prevent child deaths.

Her passion to change people’s perspectives enabled her to communicate complex scientific theory and results in a way that was engaging, not only through scientific papers, but also through several accessible books, a TEDx talk, and her fabled “plastic poo” speech at the UN in 2003. She frequently appeared in broadcast and print media and was awarded the health communicator of the year award in 2009 by the BMJ in recognition of her achievements.

She had a talent for conceiving research that would capture the public’s attention, and once hooked, would communicate clear and important public health information. One example was swabbing commuters’ hands in the UK to highlight widespread faecal contamination. As she had planned, the results were picked up extensively by the media and she was able to raise awareness of an important public health issue.

I had the pleasure and privilege of collaborating with Val on a major study on hand hygiene in British motorway service stations. The rates of handwashing with soap were horrifyingly low: around 60% in women and only 30% of men, but higher on average if there were other people around in the washbasin area.

One cannot overstate Val’s influence in pushing hygiene up the global health agenda. She played a critical role in having hygiene included under the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, co-founded the Global Public-Private Partnership for Handwashing (now the Global Handwashing Partnership), helped establish Global Handwashing Day, co-developed the Behaviour Centred Design model for behaviour change, and worked with organisations in over 70 countries on the design and evaluation of innovative Wash interventions.

Her most recent achievements included helping design the Tanzanian government’s national sanitation programme, leading to a significant increase in toilet building. The pride of her career was her involvement as a behaviour change adviser to the Indian government’s Swachh Bharat campaign to end open defecation in India, which resulted in the extraordinary achievement of building more than 85m toilets in just five years.

Val was born in Seascale, Cumbria. Her father, Geoffrey Curtis, was a physicist at the UK Atomic Energy Authority, and her mother, Margaret (nee Snelling), a keen botanist and environmental scientist. She and her two brothers grew up in Helsby, Cheshire, where she attended the Queen’s school in Chester. At Leeds University in 1980 she gained a BSc in civil engineering (chosen because her father told her girls could not be engineers). She completed her PhD in anthropology at Wageningen University, in the Netherlands, in 1998.

In 2004 Val met her intellectual and life partner, Robert Aunger, at LSHTM, and they became a powerful public health duo, co-authoring books, papers and designing behaviour change campaigns together.

Val was political and made no apologies for this. She chose a career in public health research because she loved science but also because she believed it could lead to a better, fairer world. In July, she wrote a moving and personal account of her own struggle with vaginal cancer in the Guardian. She hoped that her personal tragedy might add to the momentum for a bold visionary plan for the NHS, true to its founding principles but fit for the modern day.

This summer, she was called upon to support the British government in its efforts to control Covid-19 as part of the behaviour subgroup of the Scientific Advisory Group on Emergencies (Sage). Despite her worsening health, she even attended some meetings from her hospital bed. She also became an invaluable member of the corresponding behavioural group of Independent Sage, a body not answerable to government. Her expertise, and decades of experience, were exactly what was needed as the UK struggled to contend with a disease outbreak that still threatens our health system and economy.

Val loved opera, especially Wagner, and joined her husband in a pilgrimage to Bayreuth. In her last days, using a wheelchair, she fulfilled a lifelong ambition to be surrounded by the harmonious symmetry of the Palladian villas in Italy, and insisted that all those she most loved join her in that experience.

Her first marriage ended in divorce. She and Robert married this year; he survives her along with Naïma and Abidine, and her brothers, David and Jeremy,